Welcome to ‘Have You Seen….’ a regular column exploring an interesting film that is worthy of greater attention – for good or for ill. The focus is on the underseen, the undersung or the underrated – or just those films you just need to write about. The focus is analysis more than evaluation so, expect spoilers!

Content Warning: discussion of gore, racism and racist iconography relating to the Confederacy.

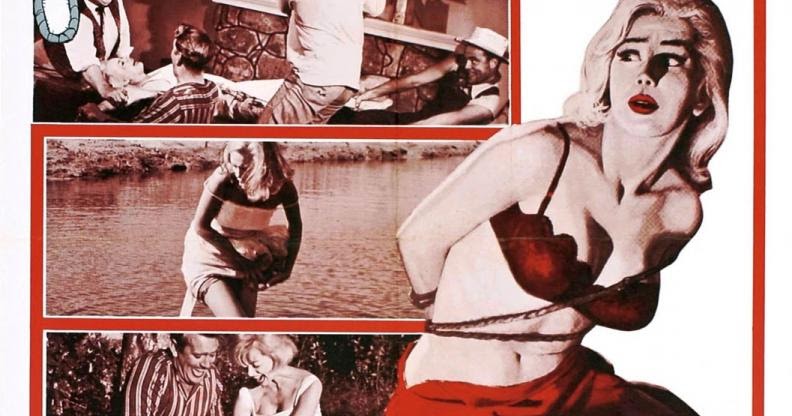

The Arrow Video release of Two Thousand Maniacs! includes an introduction from writer-director Herschell Gordon Lewis. This is Lewis’ second proper feature and solidified his status as the ‘Godfather of Gore’ (and other similar monikers). In his introduction, Lewis describes the film as his favourite film that he directed – which I like, because it is my favourite too. Two Thousand Maniacs! is definitely lesser seen than 1963’s Blood Feast (a response to Psycho that is held up as the original gore movie – you can listen to my thoughts on it on this podcast episode), and less notable than 1970’s The Wizard of Gore (a better title than a movie – the gore delivers but the film is repetitive, dull and sexist).

Why is it my favourite? Well, it is better than the other Lewis films I have seen. Why is it his? Well, Lewis explains, in the introduction, how Blood Feast was a surprise success to the extent he was left feeling he did not do enough for his audience. He sees Two Thousand Maniacs! as a more complete film, boasting of how it has a ‘beginning, middle and an end’ and touting it as more ‘philosophical’ than his previous work – and, by implication, his later work. Lewis is certainly correct that the film, unlike the shambolic (and really rather racist) Blood Feast, does feel like an actual movie. Calling it philosophical is an overstatement but is a playful recognition of a film that definitely has ambitions. Ultimately, these are sporadically achieved but, there’s something awesome about Two Thousand Maniacs!, as it exists as a precursor to the politically charged horror that has defined the modern era. Now, I am not for one second arguing that Two Thousand Maniacs! is the Get Out of 1964, I am merely arguing that it is a fascinating film that almost has something brilliant to say.

Before exploring the film, it is worth reflecting on Herschell Gordon Lewis. As a gore hound, I feel the need to praise Lewis as the inventor of the ‘splatter film.’ His dedication to putting gore on screen was a pivotal point for extreme cinema, and Blood Feast is a key text in the growth of cult film – a prime early example of a film using a critical panning to entice an audience – declaring ‘you gotta see this’ in their marketing and linking this statement to their negative press. This approach worked and, while I maintain Blood Feast is a bad film, I do have a real soft spot for it – and a lot of it is dumb fun (though too much of it is not). The endearing thing about Lewis is how self aware he is, telling Film Journal the following about Blood Feast:

“I’ve often compared Blood Feast to a Walt Whitman poem. It’s no good, but it was the first of its kind.”

Herschell Gordon Lewis

It is an endearing quotation but it does bring up the interesting debate of is doing something first good enough if you don’t do it well? But, this is a conversation for another time.

Lewis would go on to inspire generations of cult filmmakers, many of whom would go onto huge mainstream success. The early works of Peter Jackson (especially the wonderful Braindead (also known as Dead Alive) from 1992 – a film I maintain, to this day, is Peter Jackson’s best film) and Sam Raimi owe a clear debt to Lewis, because of him doing splatter first but also in regard to the gleefully hyperbolic approach to cinematic gore. Lewis started splatter and Peter Jackson coined Splat-stick, a term that could be easily applied to Lewis’ work – and that nicely encapsulates his comic sensibility. These splatter films are about fun, delighting in a lack of realism and existing as twisted carnival exhibits.

Any description of Lewis, though, would be incomplete without mentioning cinematic legend John Waters. In Linda Yoblonsky’s essay on Multiple Maniacs, for the Criterion release, she mentions how Waters stated that his ‘only objective was to make “underground” films like Andy Warhol’ but that he also cited his wider influences as ‘Ingmar Bergman, Russ Meyer and Herschell Gordon Lewis’. The inclusion of Bergman in the category of ‘exploitation heroes’ is wonderful, and seeing his name next to Lewis’ is better still. This influence of Lewis is most apparent in Waters naming a film Multiple Maniacs – a film that involves splatter gore as a clear homage. However, the influence of Two Thousand Maniacs! is perhaps more evident in 1990’s Cry-Baby – regarding the (frankly uncomfortable) visual design of the ‘Drape’ territory. John Waters himself would actually go on to make a cameo in a more modern Herschell Gordon Lewis film, the 2002 Blood Feast sequel subtitled ‘All U Can Eat’ – the early 2000s were a strange time.

For me, Two Thousand Maniacs! is where Lewis earns his influence. It is a film that sits alongside the work of Waters – though it is not as good – regarding the quality of being provocative for a purpose (in addition to provocation as its own purpose). It is this quality which raises Waters and, in this case, Lewis above filmmakers such as Tinto Brass, whom I do not have time for. Which leads me to my passionate defence of Two Thousand Maniacs!, or – more accurately, an explanation of why I love it in spite of itself.

The premise of Two Thousand Maniacs! is a wild one. The film takes place on the centenary of the end of the American Civil War and is set in the fictional town of Pleasant Valley. This town is putting on a centennial celebration – which later turns out to be really the anniversary of the day a band of Union troops slaughtered the town (this is a major misstep of the film that I will deal with later) – and their actual plan is to lure six ‘Yankee’ tourists into the town so that they can kill them in elaborate ways as part of their festival. Realistically, it is all an excuse for gory set-pieces involving cannibalism, mutilation and consistent over the top gore. Like with Blood Feast, Lewis is seemingly unable to show the violence happening, instead showing the injuries caused. There are some notable exceptions here but, special effects are difficult so why not have an axe come down on something out of shot and then wave a prosthetic arm around? Much easier than faking an actor losing an arm. This approach adds to the endearing quality of Lewis’ films, cementing the gore as patently ridiculous.

The aesthetic of Pleasant Valley is very purposeful. Every resident, adult or child, proudly flies Confederate Flags – in fact, they are everywhere. It is overwhelming and deeply uncomfortable, and is accompanied with a sunny and positive aesthetic that evokes celebration. On the surface, it all seems fine, but this surface is used to display what the flag actually means and how it cannot be divorced from context. These flag wavers are already framed as in the wrong by a title that makes it clear what the filmmaker thinks about these residents. The brilliance of the film though is in how it presents the façade first and then gives us a reality. This happy display of celebration is what allows the residents to take advantage of their guests. Those that arrive – and they only arrive due to false detour signs being put up – are actually eager to leave and get on with their lives. However, the Pleasant Valley residents go out of their way to show their hospitality, offering free accommodation and positions as the guests of honour in their celebration. The real meaning of this is clear to the audience and therefore we see the façade in action: the outward show of hospitality is a way to exert cruelty. It is a nice metaphor for the fact that this obsession with Confederate iconography, and with the myth of the South, is just a smokescreen for intolerance.

It is no coincidence that this flag waving town are still trying to enact violence due to the Civil War, and still trying to ‘get even’. The opening song declares ‘the South will rise again’ – articulating the myth – and showing the intrinsic link between confederate iconography and confederate values. This point is hammered home even clearer by the wider presentation of the townsfolk. The whole film leans into caricature and the Southern citizens (of this town) are uniformly represented negatively. They are shown as simple, backwards and cruel. In the very opening, there is an incredibly charged – and uncomfortable – sequence of children playing with small nooses as toys (before, off screen, hanging a black cat). This is framed as cruel and uncomfortable and does foreground, though does so crudely, a political viewpoint. At no point are we supposed to sympathise with these people – even when we are entertained by the gore. Interestingly, we do leave the town (later in the film) and meet another Southerner who is not coded in the same way as the Pleasant Valley residents. Thus making it clear that the film is not anti-South; the film is against people who still praise the Confederacy and push its iconography. It criticises people who push the myth of the South, wanting to separate the Confederacy from racism and general prejudice – a separation the film shows as impossible.

This is where we encounter the film’s core issue though – an unnecessary detail that can be analysed interestingly but does, by itself, bring an unfortunate connotation. The film needs to make it clear that the citizens of this town are obsessed with the Confederacy and thought that it was right. It needs to show that the cruel values of the Confederacy exist in them – and by capturing and brutally murdering people while happily waving Confederate flags, it definitely shows this. Sadly, Lewis decides to add a twist to the film that actually gets in the way. This is a fictional town obsessed with a very real thing. However, when we learn their want for vengeance comes from their town being slaughtered by Union forces, the issue is reframed. The townsfolk are clearly not in the right in wanting to kill random Northerners, but it is positioned as being a disproportionate act of vengeance. Rather than presenting modern day Confederate supporters as just plain cruel, it reframes the film as being about cycles of violence that are divorced from politics. This inherently places the people of Pleasant Valley as victims and is only further enforced by the final twist which reveals them to also be ghosts. The town no loner exists, it has just come back as a ghost to wreak vengeance one hundred years later (and probably does this every year). Annoyingly then, the sin that is being punished is not the sin of the Confederacy, it is a sin of Union forces.

Realistically, this plot point should just not be here. For this reason, I would love a modern remake that keeps all that is brilliant about Two Thousand Maniacs! and omits this detail that scuppers this greatness. It stands out as a moment where Lewis clearly just wants to put in a gotcha-twist but instead ends up going against how he has framed the rest of the film. Because, this aside, the film is awesome – if very rough around the edges. Some of the horror also feels very modern, especially the gaslighting elements. A great moment is when the captive visitors are unable to make phone calls that reach outside of the town, as long-distance calls are blocked and the local Sheriff hi-jacks the phoneline and pretends to be the external person our captive is calling. This moment is especially important as it reinforces the propensity for the residents to lie and to manipulate, which is key to the film.

Actually, the best way to read the excuse given by the townsfolk – of a slaughter by Union troops – is as a lie. The framing of the Pleasant Valley residents the whole way through is politically consistent. The iconography is very deliberate and it all fits together into a blunt but coherent statement. We also know they lie and manipulate and this links back to the central argument being pushed that those that invoke the Confederacy use excuses and facades that actually mask a very real intolerance and cruelty. We only have a monument as evidence of a Union attack and it seems incongruous even in the film. When the event is referred to later, by the external police officer, it is given the description of a mysterious or folkloric moment. The tale is told as if it is a rumour. This functions as a way of laying the foundations for a supernatural twist but actually gives good evidence for this event being an excuse – and a lie. Therefore, the ultimate thesis is a very engaging one: that the cruel Confederate supporters are constantly hiding behind excuses and lies. This makes the film feel searingly contemporary in a time when there is a widespread, and abhorrent, movement to display and use Confederate iconography and to argue, erroneously, for positive elements. Two Thousand Maniacs! shows these people, in 1964, and uses the blunt language of exploitation cinema to show the actual cruelty that exists here and how their claims are empty lies.

All this being said, I know that this is a generous read. Fundamentally, the film needs to make this more explicit than it does and therefore delivers its message poorly, if it delivers it at all. However, there is still something brilliant here that makes Two Thousand Maniacs! a fascinating film. Yes, it is flawed and its use of racist iconography – and potential presentation of the Confederate South as victims – is more than enough to write the film off. But, there is still gold in this film that feels ahead of its time. It is a very flawed gem but it does enough to easily establish itself as my favourite Herschel Gordon Lewis film. Do you need to watch it? Probably not. Is it worth watching? I think so.

Reblogged this on shoveling paragraphs and commented:

fascinating thematic exploration of a little known 60s gore film.

LikeLike