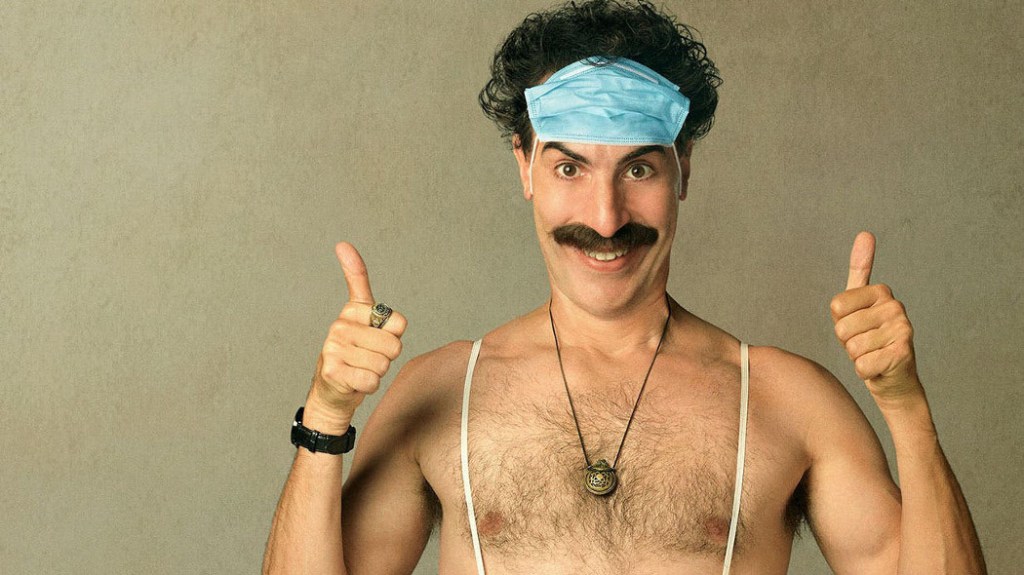

Fourteen years after Sacha Baron Cohen first brought Borat to screens, the character returns with a more overt purpose. Though the previous film was a satirical comedy based on revealing xenophobia in the United States, it is very telling that the political nature of this sequel has surprised people. Though it is easy to say that Borat was always political and people did not notice, that is slightly evading the real truth: a lot of the original Borat missed the mark, speaking to the intolerant rather than confronting them.

To a lesser extent, the same is true of this sequel. There is a selection of very smart and very political moments that expose hypocrisy and genuinely confront people in need of confronting. However, astute satire is never far away from easy gags, broad comedy and the awkwardly unfunny. Borat: Subsequent Moviefilm hosts a comedic sensibility that is often at odds with its political sensibility, the core issue being that the humour and the politics do not feel intelligently intertwined – outside of some standout moments. The repeating structure is a lot of crude humour and caricature that builds up to a political moment that exists, usually, in separation from what came before. An additional issue for me is that I do not find Borat very funny. I am certainly not against it but it just does nothing for me and, frankly, just feels old. Cohen’s Borat feels like a relic that gets in the way and a figure that does not fit in with what is being told. However, as much as the original Borat was not for me, the character was invented to match a specific purpose and was a suitable fit. Here the targets are the Trump Administration and normalised misogyny – worthy targets for sure. However, these targets do not fit naturally alongside Borat and transferring him to this new context feels a bit laboured.

This all being said, there is one big plus to Borat: its ability to perhaps work as a Trojan horse. Though a lot of people celebrate the first Borat for the way it lampooned racism, it has had a wider cultural impact of people regurgitating racist lines out of context and gravitating only to the puerility. Whether this is on the film or on the audience is a conversation for another time (I maintain that it did not do enough, consistently, to avoid the trap of just ending up being the thing it was satirising). Now, that original audience is being brought to this sequel by this character. Though Borat was a huge success, other Sasha Baron Cohen projects have not been, therefore the Borat character grants it an audience that it would otherwise not have – and Cohen and his collaborators clearly wants their film to be watched. The story focuses around Borat trying to gift his daughter to Mike Pence, which is just an excuse to open up a lot of situations where Borat exposes what the American right are willing to say or do. There are points where clear hypocrisy is shown and Cohen’s ability to manipulate his subjects into humiliating themselves, often via other characters more than through Borat, is commendable. Therefore, the broad appeal of Borat is used to confront an audience that may not be ready to be confronted. An already famous scene, taking place late in the film, involving Rudy Giuliani clearly exposes the man’s misogyny, lack of substance and plain creepiness – and is presented in such a way that makes it almost impossible to ignore. If nothing else, humiliating a key member of the Trump campaign before the election – and during the voting period – is a smart move even if all it does is generate headlines.

However, this sequel just does not do enough with its Trojan horse premise. Borat may be our gateway to this world but the character still holds it back. We open in Borat’s Kazakhstan and once again the country is a punchline. Yes, it is supposed to lampoon prejudiced and ignorant views of marginalised nations but all it does is reflect them. Those who already know that popularised views of Kazakhstan are completely ignorant will recognise the presentation here as hyperbole; those that see Kazakhstan this way already will laugh along and will not be challenged. This is the core issue of the film: if you are already in on the joke – if you already agree with Cohen’s wider politics – you will get it – and nothing is really done; if you are the audience that Cohen is trying to educate and expose, you are likely to just focus on crude sexual humour and laugh at the funny foreign man with the funny accent.

Luckily, the film does transcend this – the American content presenting comedic setups in which the punchlines will not be missed – but Borat’s caricature does always feel like a weight around the film’s neck. Yes, he has brought in the audience that will be challenged by later content but, fundamentally, the later content is not challenging enough. In our ever changing political climate intolerance is now so public that the Sasha Baron Cohen style of satire just does not really work. Cohen coerces people into revealing their horrible views on camera which, in 2006, was very shocking. Now, in an age defined by streaming video, we are inundated by people saying much worse things to camera all the time, and not being coerced into saying it. Yes, Cohen sets up a scenario where Giuliani says horrible things on camera – but the actual President, and key figures across the world – say the worst things, consistently, with no shame. Cohen’s attempts to reveal that the emperors have no clothes have no impact when those being targeted are already proudly walking around in the nude.

The shining star though, and the thing that almost saves the film, is Maria Bakalova’s Tutar (Borat’s daughter). The majority of the film is not Borat pranks, it is actually focused upon building a father daughter relationship – and this is where the film is at its most successful. The growing connection is very sweet and it is used to show a learning process that lampoons misogyny. We get an actual example of Borat, and his daughter, learning that their societally influenced views are just wrong – using a caricature of misogyny to actually reveal real misogyny in America. This process is sweet and well handled, though it is continually derailed by lapses back into Borat shtick and an unfocused narrative progression. Bakalova is the star of the film here, she commits very hard to her role and her character is much more in line with eliciting the content the film is based around than Borat is – almost as if she was designed for the film that exists whereas Borat is just a holdover from something else. Really, this should be a Tutar film, as she is the character made for the message – and therefore conveys it well – but Borat has to be here to get the audience. It is very telling that, in a film that wants to expose misogyny, the narrative has to centre around a male figure in order to be successful. This is a sad truth that exists outside of the film but, really, I would respect the film more if it was not trying to challenge the misogynists by placating them. Borat could be in the film much less, just the name that draws you in, and the film still boils down, far too frequently, to misogynist thing as a punchline – it may be mocking misogyny but the misogynists are still laughing.

Ultimately, this Borat sequel feels rushed and rough around the edges. In a way, that works for it: it is a film put out there with a clear political purpose and the expediency of release overruled everything else. However, this noble intent is underscored by a weak execution. There are moments in this film that are brilliant – the interview, a rally and a ball scene really standing out as clever mixes of humour and intent – but even these high points are squandered by incongruous comedy getting in the way. The film can be funny, and is often political, but rarely both at the same time. This mismatch cuts at both sides of the equation; the film is not funny enough to be a successful comedy and the political points do not hit hard enough to elevate it, and, beyond this, the film just feels at war with itself. There is a lot to respect and admire here, and it could be important at this specific moment, but it is not a, dare I say, “great success!”